Seven years after she founded the

nurses’ training school in Brussels, the clouds of war gathered over Europe.

And yet she did not seek safety in her native England. When the German army

marched into the Belgian capital on 20 August 1913, she stood watching among

the ‘sullen and silent’ citizens.

Just over a year later, a German

chaplain, Pastor Le Seur sits with her in her cell in the St Gilles Prison.

‘Can I not show you some kindness? Please do not see in me now the German, but

only the servant of our Lord.’

The next morning, 12th

October 1915, she was executed at dawn for helping Allied soldiers escape to

neutral Holland. Pastor Le Seur prayed with her before the shots rang out.

And so died, at the age of 49, Edith

Cavell.

Pastor and condemned woman, united by

their faith in the same Lord. It underlines the blasphemous obscenity of war:

each side Christian, each side mercilessly killing the other’s youth.

Edith Cavell was a vicar’s daughter,

born in Swardeston, near Norwich. She worked first as a governess (including a

spell with an affluent Brussel’s family) before training as a nurse. In 1907 she

was invited to establish a pioneering training school for nurses in Belgium

where she showed herself to be a skilful teacher, administrator and carer.

Many of us today are aware of gathering

clouds of international tension. We feel threatened by global economic

collapse, intractable political problems, and the possibility of nuclear

conflict in the Middle East. Some Christians with a particular view of Bible

prophecy saw last week’s ‘blood moon’ as a sign of impending calamity.

In these fraught times, Edith Cavell

reminds us that there have been many crises in the past, when some Christians

have felt that the end must surely be near, and were mistaken. But she also

teaches us how to live in difficult times.

She told her nurses that they must treat

friend and foe alike. But she also became involved in an underground network

helping allied soldiers (her ‘lost children’, she called them) to escape over

the Dutch border from where some made their way back to the trenches via England.

She was arrested in August 2015, tried as a ring-leader of the network, and

sentenced to death.

We have an insight into her inner life

because she regularly read The Imitation

of Christ, a 15th-century devotional book by Thomas à Kempis and

marked passages of particularly significance to her. She was a woman who sought

to be an imitator of Christ.

Like Christ, she found the mission she

had glimpsed when she was younger: ‘someday, somehow I am going to do something

useful.’ Like Christ she loved and served others: ‘I have loved you all, much

more than you can know,’ she wrote to her nurses from her cell.

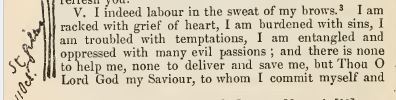

Like Christ she did what was right even

when it brought her into conflict with the authorities. Like Christ, she faced

death with faith: on the night before her execution she marked a passage from à

Kempis – ‘There is none to help me, none to deliver and save me but Thou, O

Lord God my Saviour.’

‘I die for God and my country,’ she

declared the next morning, facing her executioners. But why? Why does God not

save her? Why is she felled by those merciless guns?

I think in times of chaos we often look

for ‘top down’ intervention by God, something dramatic, unmistakable. But often

God works from the bottom up. Movements begin with people on the ground,

perhaps simultaneously in different parts of the world who have a vision that

the wind is changing direction and run with it, even at great cost.

|

| Cavell Gardens in Inverness |

Often God’s change comes as people on

the ground are changed and seek to be imitators of Christ, working out what

that means at the heart of their ordinary lives. We fear economic collapse, the

failure of power and fuel supplies, empty shelves in the shops, and we fear

desperation and anarchy. What would it mean in those scenarios to be imitators

of Christ, agents of change?

Thomas à Kempis sought to imitate Christ

by turning from the world. Edith Cavell turned inwards and reflected on her

soul and her God, but she also reached out, engaging in love with a chaotic

world, and seeking to save some, and in this her imitation of Christ was more

rounded than his.

For Jesus’ mission was one of bottom-up

change. The shoots of new life sprang from the darkness of an empty grave, and

began a spiritual movement which will continue until that day when wars cease.

Wrote

à Kempis ‘After winter followeth summer, after night the day returneth,

and after a tempest a great calm.’

(Christian Viewpoint column from the Highland News dated 8th October 2015)